Dietary Fibre Types and Their Role in Gastric Emptying and Satiety Signalling

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

Overview of Dietary Fibre Types

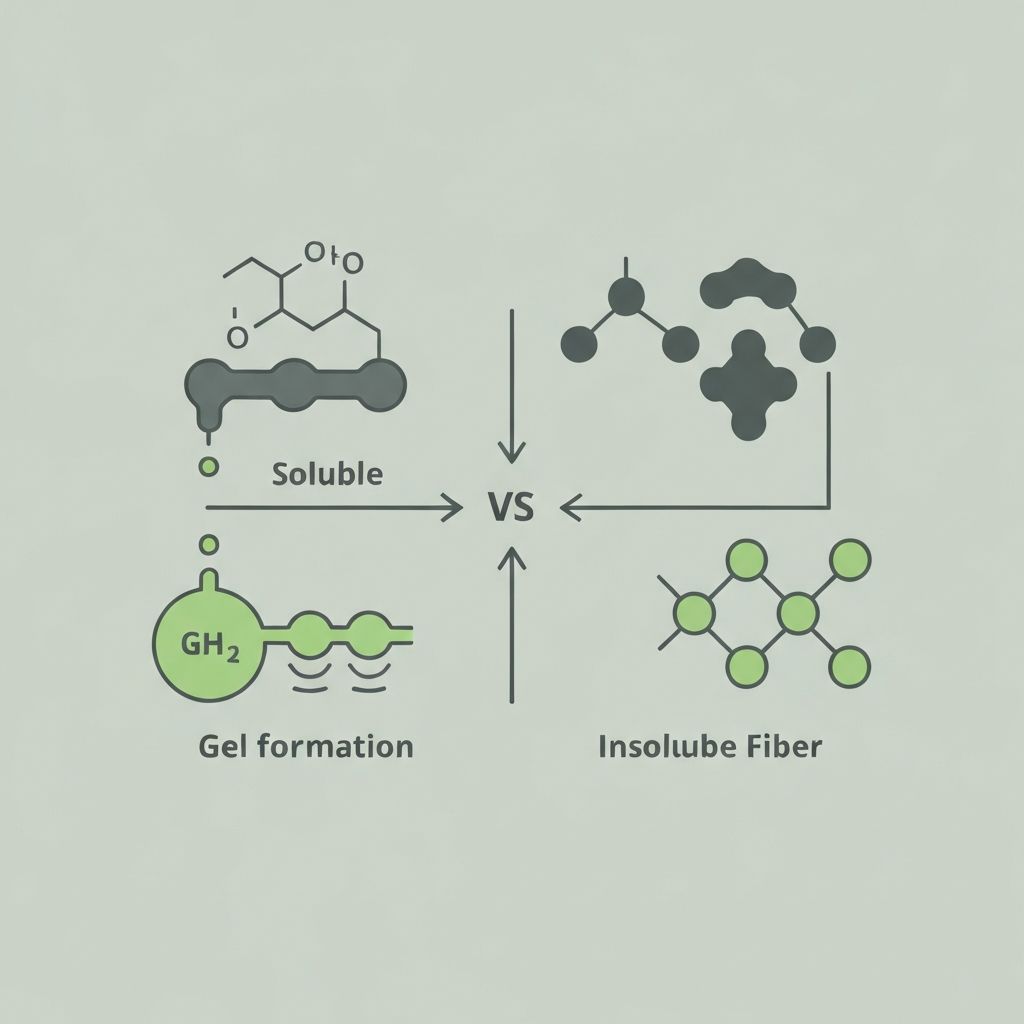

Dietary fibre comprises polysaccharides resistant to digestion in the small intestine. Classification systems distinguish between soluble and insoluble fibres based on water solubility, and between fermentable and non-fermentable fibres based on colonic bacterial metabolism.

Soluble Fibres

Dissolve in water to form viscous gels. Examples: beta-glucans, pectin, inulin. Slow gastric emptying and nutrient absorption. Readily fermented in the colon.

Insoluble Fibres

Resistant to water dissolution. Examples: cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin. Promote faecal bulk. Less readily fermented but contribute to transit.

Gastric Emptying Mechanics

Gastric emptying rate determines the temporal pattern of nutrient delivery to the small intestine. Viscosity and gel-forming properties of soluble fibres modulate this process through multiple mechanisms:

- Increased gastric distension from gel volume

- Delayed gastric mechanoreceptor signalling

- Enhanced cholecystokinin (CCK) secretion from nutrient sensing

- Reduced antral contractions via neural feedback

This delayed transit extends nutrient availability to satiety-sensing regions and allows prolonged interaction with small intestinal nutrient sensors.

Water-Holding Capacity of Insoluble Fibres

Insoluble fibres absorb water within the intestinal lumen, increasing faecal bulk and transit rate. The bulking effect distends the colon and rectum, stimulating mechanoreceptors that generate satiety signals independent of nutrient absorption.

Colon distension modulates vagal afferent signalling to the nucleus tractus solitarius, influencing subsequent feeding behaviour. Water absorption capacity varies by fibre source: cellulose holds approximately 2–3 g water per gram fibre, whilst insoluble pentosans hold greater quantities.

Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production

Fermentation of dietary fibre by colonic bacteria yields short-chain fatty acids (SCFA): butyrate, propionate, and acetate. Fermentable fibres—particularly beta-glucans, resistant starch, and inulin—support microbial growth and SCFA synthesis.

Fermentation of soluble fibres yields SCFA proportions: acetate (60–70%), propionate (15–20%), butyrate (5–10%), depending on substrate and microbial community.

SCFA and Satiety Hormone Release

SCFA, particularly butyrate and propionate, act on G-protein coupled receptors (GPR41, GPR43) on colonocytes and enteroendocrine cells. This receptor activation stimulates secretion of satiety peptides:

| Hormone | Primary Source Cell | SCFA Trigger | Satiety Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 | L-cells (distal ileum, colon) | Propionate > Butyrate | Slows gastric emptying; increases insulin; enhances vagal signalling |

| PYY | L-cells | Butyrate > Propionate | Inhibits ileal contractions; promotes satiety sensation |

| CCK | I-cells (small intestine) | Indirect (via nutrient sensing) | Signals postprandial satiety; slows gastric emptying |

Combined Effects with Protein and Fat

Fibre does not act in isolation. Co-ingestion of fibre with protein and fat modifies the glycaemic and insulinaemic response, alters postprandial amino acid kinetics, and potentiates satiety signalling:

Protein + Fibre

Delays amino acid absorption; reduces postprandial aminoacidaemia spike. Both nutrients stimulate CCK. Synergistic satiety effect.

Fat + Fibre

Fibre dilutes fat energy density. Fat stimulates CCK and GLP-1 independently. Combined effect: prolonged nutrient signalling.

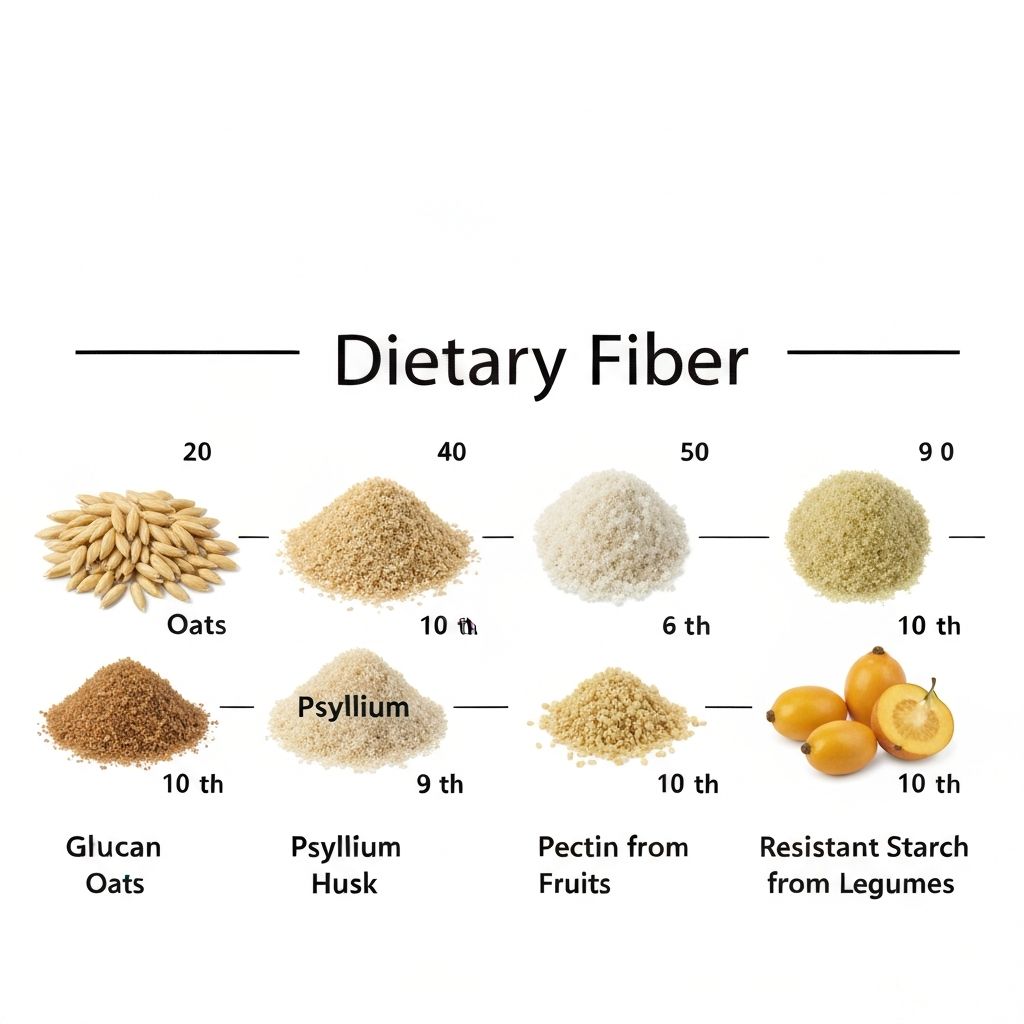

Research on Different Fibre Sources

Evidence from randomised controlled trials and observational studies demonstrates variable effects of different fibre types on satiety and feeding behaviour. Key findings:

| Fibre Source | Type | Fermentability | Evidence for Satiety |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-glucan (oats, barley) | Soluble | Highly fermentable | Moderate; viscosity delays gastric emptying and glucose absorption |

| Psyllium husk | Soluble | Slowly fermentable | Moderate-to-strong; high water-holding capacity creates bulking effect |

| Pectin (fruits) | Soluble | Readily fermentable | Weak-to-moderate; rapid fermentation may limit sustained effect |

| Resistant starch | Soluble/Insoluble | Readily fermentable | Moderate; SCFA production; potential second-meal effect |

| Cellulose | Insoluble | Non-fermentable | Weak; mechanical bulking only; no SCFA contribution |

Links to Detailed Fibre-Satiety Articles

Explore in-depth exploration of specific fibre types and their physiological effects:

Soluble Fibres and Gastric Emptying Delay

Viscosity mechanisms and gel formation in the stomach and small intestine.

Read the article →Fermentable Fibres and SCFA-Mediated Satiety Signals

Colonic fermentation pathways and hormonal responses to short-chain fatty acids.

Read the article →Beta-Glucan and Oat-Based Fibres in Satiety Research

Clinical trial data on viscous soluble fibres from cereal sources.

Read the article →Psyllium Husk: Water-Holding and Fullness Effects

Physiological observations of high-capacity water-absorbing fibres.

Read the article →Resistant Starch and Second-Meal Satiety Phenomena

Glucose response and persistent satiety signalling from starch fermentation.

Read the article →Combined Macronutrient Effects on Satiety Cascade

Fibre interactions with protein and fat in multi-nutrient meals.

Read the article →Common Patterns in Satiety Studies

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of satiety research reveal consistent patterns in visual analogue scale (VAS) findings and energy intake outcomes:

- Soluble fibres consistently reduce hunger ratings and subsequent energy intake (range: 4–14% reduction in next meal consumption)

- Insoluble fibres show weaker effects on subjective satiety but contribute to colon distension signals

- Fermentable fibres demonstrate delayed onset of satiety effects (peak SCFA production: 4–8 hours post-ingestion)

- Individual variation in microbiota composition and SCFA production capacity accounts for 15–30% variance in satiety responses

- Adaptation may occur over 2–4 weeks of regular fibre consumption as microbiota composition shifts

Frequently Asked Questions

What distinguishes soluble from insoluble fibre mechanistically?

Soluble fibres dissolve in water to form viscous solutions that slow gastric emptying and nutrient absorption rates. Insoluble fibres resist water dissolution and function primarily through mechanical bulking and receptor-mediated colon distension. Fermentability is independent of solubility.

How do SCFA contribute to satiety if they are absorbed post-colonic?

SCFA interact with GPR43 and GPR41 receptors on enteroendocrine L-cells before absorption. This triggers local GLP-1 and PYY secretion into the portal circulation. The hormones, not the SCFA themselves, signal satiety to the central nervous system.

Does fibre type matter more than total fibre quantity?

Both quantity and type contribute to satiety outcomes. Total fibre influences faecal bulk; fibre type determines viscosity, fermentability, and satiety hormone profiles. Current evidence suggests soluble and fermentable fibres produce stronger satiety effects per gram than insoluble non-fermentable sources.

Are satiety effects from fibre immediate or delayed?

Viscous soluble fibres produce immediate effects (within the meal, via gastric distension). Fermentable fibres produce delayed effects (4–8 hours post-ingestion, via SCFA-mediated GLP-1/PYY secretion). This temporal profile varies by fibre type and individual microbiota.

What research limitations constrain evidence for fibre-satiety relationships?

Study heterogeneity in fibre dosage, duration, participant demographics, baseline microbiota, and satiety measurement methods (VAS, food intake, appetite hormones) complicates meta-analysis. Most trials are short-term (<4 weeks). Long-term adaptation data are limited. Mechanistic studies often involve small samples.

Continue Your Exploration

Learn more about the physiological mechanisms underlying gastrointestinal function and satiety signalling.

Explore Related Research